City Limits asked readers and members of the city’s education community to fill out a survey about the policy, which is set to expire at the end of June. We heard from nearly 90 respondents, including dozens of current and former parents, educators and advocates. Here’s what we found.

Adi Talwar

P.S. 246 Poe Center located in the Bronx.Mayor Eric Adams visited Albany last week in a bid to convince state legislators to renew the current term of mayoral control of New York City’s school system.

The policy–which has been in place for the last 20 years, and gives the mayor the power to appoint most members of the city’s Panel for Educational Policy, as well as hire and fire the schools chancellor–will expire at the end of June. State legislators have just a few days left in their current session to act on it.

As Adams asks the legislature for four more years of what he prefers to call “mayoral accountability,” many stakeholders in the education community say they have issues with mayoral control, according to an informal survey about the policy that City Limits asked readers to fill out over the last several weeks. Here’s what we’ve heard from respondents so far.

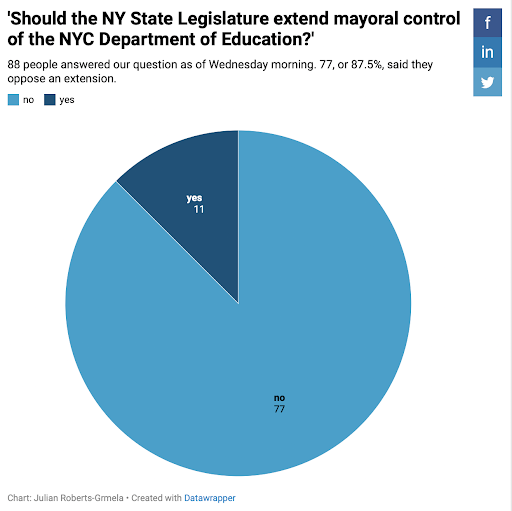

The vast majority of respondents indicated that they were opposed to an extension of mayoral control. Of the 88 people who opted to complete the survey as of last Wednesday (May 18), 87.5 percent, or 77 people, responded “no” when we asked if state legislators should extend the current policy. The 11 others responded “yes,” indicating they were in favor of an extension.

The survey was distributed on social media, in our weekly newsletter and in this call-out on our website. The “yes” or “no” question about an extension was the only required question in the survey, but others were included encouraging respondents to describe their relationship to the New York City education community and to explain the reasoning behind their opinion on mayoral control.

The 88 respondents included dozens of current and former parents and grandparents, 11 current or former Community Education Council members, 16 people who identified themselves current educators or DOE employees, as well as advocates, a social worker, a school nurse and an occupational therapist, among others.

In an interview with City Limits earlier this month, State Sen. John Liu, chair of the Standing Committee on Education, said the legislature will probably end up amending mayoral control to maintain “accountability” while increasing parental engagement. (The current policy, established two decades ago, replaced a previous arrangement where decisions fell to a seven-member Board of Education, with input from 32 elected school district boards—a system Mayor Adams has described as rife with “patronage, corruption, infighting, failing our students.”)

“It’s unlikely that we’re going to simply allow the law to expire without any action, because that would bring us back to the pre-2002 system. Nor is it likely that we’re going to do what the mayor and the governor wants, which is a four year extension with no changes,” Liu said. “I expect the solution to be one that allows the mayor to retain control and therefore be held accountable by the public, by parents, by legislators and at the same time, provides a stronger, more meaningful mechanism by which parents can inject their input and have responsiveness from the Department of Education.”

Liu says the legislature’s decision will be based on community feedback.

“We’ve listened to all forms of communication, whether it be by email, or by telephone,” Liu said. “I have had people drop in, we’ve had organizations meet with me in person as well as by Zoom. And we try to keep up with the social media communications, although that’s not a perfect way to do things. But we’re listening.”

Here is what our survey respondents said about the issue in the optional short response section.

In favor of an extension

One educator responded that they favor an extension of mayoral control because of Adams’ new, phonics-based approach to teaching reading. That initiative, unveiled earlier this month, will for the first time screen all city students for dyslexia—a learning disability the mayor dealt with himself as a student. “We are going to do things differently,” Adams said in announcing the new plan. “This is our opportunity to really move the needle on something that has been impactful for our children for a long time.”

The respondent said they think Adams is off to a good start, and should be given a chance to lead the system—the same argument the mayor himself has made.

“I need mayoral accountability to continue the work that we have done in the last few months, and I think there’s an appetite to give us the mayoral accountability that we need,” Adams said in a press briefing last week.

Two other respondents in favor of continuing the current system said they think centralized leadership is necessary for efficient decisions to be made in the nation’s largest school system. Others said they want Adams to remain in charge for the sake of consistency, as students are struggling to recover from over two years of disrupted learning due to the pandemic.

Two said they favor mayoral control, because without it, New York City schools may not have fully reopened for in-person instruction this year. Others said they favor the policy because it allows them to hold the mayor accountable.

The most common theme for why people answered “yes” was because they said it is better than any alternatives they were aware of.

The opposition

Respondents opposed to an extension mentioned a couple of common themes. Some said they were opposed to mayoral control because they feel it is undemocratic, and that one person should not have executive authority over a system as large as the Department of Education.

Respondents also mentioned the diverse needs in different neighborhoods and school districts across the city, which they suggested requires more ground-level leadership. This was the most commonly shared reason for those opposed, who said the system does not allow for the education community to adequately participate in school policy decisions.

Some said they believe mayoral control is a racist policy since more white, affluent school districts have democratically-elected school boards, while mayoral control has been used to take away community control in predominantly Black and brown school districts like New York and Chicago.

Others referenced what they considered negative results of mayoral control for the last two decades, like the expansion of charter schools and the focus on standardized testing. Some said they feel the policy results in an education system that is “too political,” and where consequential decisions are made too suddenly.

Some respondents said they’re opposed to mayoral control because they think the mayor –– who has no education experience –– is not qualified to lead the education system. They said educators, families and students should be the ones with decision-making power.

When it came to suggested alternatives, some respondents suggested returning to the community school board model that was in place prior to 2002. Others suggested extending mayoral control for a minimum amount of time –– like one year –– with the purpose of preparing a viable alternative when that short extension expires. These folks said they hope the legislature commissions a task force to evaluate mayoral control and create a new system.

The state legislature has until the end of June until the current policy expires, though lawmakers are expected to wrap up the current legislative session in just a week.

In a policy paper released last week, education experts with the New York Civil Liberties Union proposed reforming the city’s Panel for Educational Policy, which votes on major educational decisions; the majority of the panel’s members are appointed by the mayor.

The NYCLU suggested allowing other elected officials, like the city’s public advocate and comptroller, to appoint their own PEP members, and said that a majority of the seats “should be reserved for people with demonstrated ties to public schools, like current or retired educators, public school parents, staff, and recent graduates.”

“The flaws of our mayoral control system have been widely understood for two decades. We don’t have to keep ignoring them,” the report reads.

8 thoughts on “You Told Us: Should New York Extend Mayoral Control of City Schools?”

Even though the majority of citizens oppose mayoral control, the spineless legislature will no doubt extend it. I guess they believe in no accountability and not checks and balances. Neither the current mayor nor chancellor has done anything to support the schools in 5 months, and with mayoral control extended, the public school system will go down the drain. If this were Westchester or Long Island, this would never happen.

I’m a retired NYC Public School Educator who, spent almost 30 years servicing our wonderful children in the school system. I watched the devastating and failed results of mayoral control and the catastrophic damages that were done are are still being done to our helpless children; some of whom have parents who don’t fully understand the system and are being taken advantaged of. We need to definitely end mayoral control and return to the individual school districts headed by a superintendent and a locally elected school board, which are closely linked to the constituencies that they serve. Mayoral control is a racist system, which is designed to deprive some of our most neediest children of the services which they need!

Some thoughts:

1. The claim that the “majority of citizens” oppose mayoral control seems obviously false to me. City Limits readers don’t represent the majority of voters, most of whom probably don’t know enough about the issue to have an opinion.

2. Mayoral control seems obviously MORE democratic to me than the alternatives. Why? Because the mayor is someone most voters have heard of; by contrast, very few voters are likely to have heard of school board members (or for that matter, ANY public official who isn’t citywide or statewide!) It seems to me that control by a well-known public official is more democratic than control by unknown officials.

3. And since the mayor is Black, the notion that mayoral control is “racist” is obviously moronic, and anyone who plays the race card here cannot really be taken seriously.

4. The claim that mayoral control has been terrible for the schools strikes me as probably wrong, because other big cities do NOT have mayoral control and their schools aren’t worse than ours. If you look at test score data, NYC is actually pretty average for urban school districts- not the best, not the worst. (https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_221.80.asp?current=yes )

In sum, the case for mayoral control is that it is more democratic and not obviously harmful.

On the other hand, there is one plausible argument against mayoral control: that the mayor is not an expert, and that school boards are more likely to listen to the real experts than a mayor who has 20 other issues to worry about, or a mayor-appointed chancellor who might be a crank. Based on a quick Google search it seems to me that reasonable people disagree on this point. My off-the-top-of-the-head guess is that because U.S. urban schools have poor reputations whether they are led by mayors or school boards, it probably makes very little difference who appoints the leadership.

Parent and grandparent of two generations of public school education for family weighing in. No fond memories of chaotic and corrupt local school board control. On the other hand a one size fits all approach in a homogenized curriculum is also a big fail (a la’ Bloomberg, etc.).

So what does work? Small twenty student class cohorts where the educator can address individual student needs based on their sensory guided learning abilities. No fantasy frills promoted by extreme pedagogic corporate shills but attention to using the strengths of each students capabilities.

Guess what this is one of the methods successfully used in many “Charter Schools’. Education factories that are overcrowded and poorly supported are guaranteed to fail. The current corrupt city leadership is promising a pig in the poke.

Grandfather and father to two generations of seven public school students. Lived through the period of community school boards which for the most part fell to chaos and corruption. Nor did the homogenized curriculum of mayoral control succeed in the recent period.

So what does work? Follow the practices of the charter schools with twenty student limits in each class so the teacher can adjust for the individual sensory adaptations of each student. The overcrowded classed of our present schools cum learning factories are doomed to fail.

Great article!

Even though the majority of citizens oppose mayoral control, the spineless legislature will no doubt extend it. I guess they believe in no accountability and not checks and balances. Neither the current mayor nor chancellor has done anything to support the schools in 5 months, and with mayoral control extended, the public school system will go down the drain. If this were Westchester or Long Island, this would never happen.