Those with past convictions prosecuted by the Manhattan District Attorney can apply to have their closed case reviewed by the new Post-Conviction Justice Unit (PCJU), what reform-minded DA Alvin Bragg called a “significant priority” for his office. “If you’ve committed the wrong person, there’s someone else out there who’s still doing harm.”

Jarrett Murphy

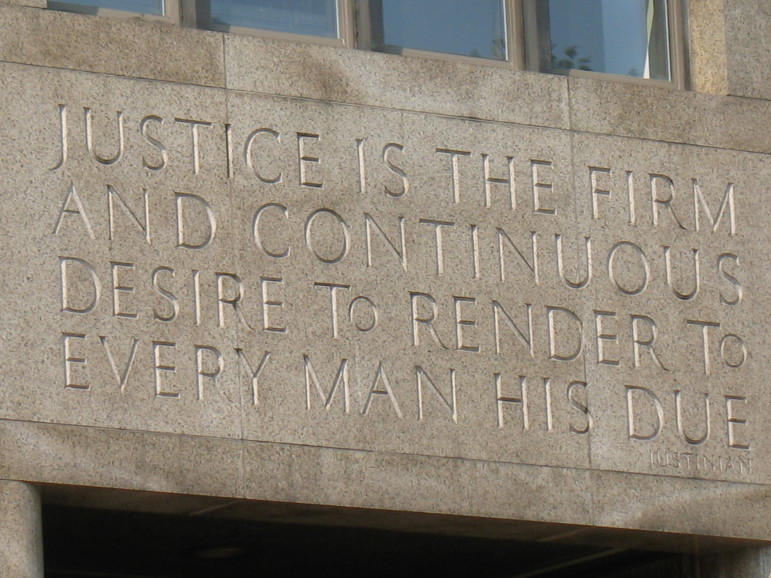

The facade of the criminal court building in Manhattan.Over the last three decades, dozens of people who were convicted of crimes in New York County have since had those convictions overturned, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, which tracks information on wrongful conviction cases from 1989 to present.

They include the five men accused and convicted in the high-profile Central Park jogger case, who were sentenced as teenagers and spent several years behind bars before DNA evidence cleared them in 2002. They include Johnny Hincapie, who alleged he was coerced into falsely confessing to a role in the 1990 fatal stabbing of a tourist on a Manhattan subway platform. Hincapie spent more than two decades in prison before a judge set his conviction aside in 2015.

Now, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg—who took on the role in January after winning a crowded race last year to replace longtime prosecutor Cy Vance—says his office is making it “a significant priority” to root out past wrongful convictions. Last week, Bragg unveiled an online application through which anyone with a closed case that was prosecuted by the Manhattan DA’s office can request to have their conviction reviewed. Those not directly involved in a case can also submit an application on behalf of another person with a past conviction.

“It’s the height of injustice if you have a wrongful prosecution,” Bragg said in interview with City Limits on Monday. “Often lost in the mix is, if you’ve committed the wrong person, there’s someone else out there who’s still doing harm.”

The reviews will be overseen by the Post-Conviction Justice Unit (PCJU), established in January within the Manhattan DA’s office but which operates separately from its trial and appellate prosecutors—independence that’s important to the unit’s integrity, Bragg said. PCJU will screen all applications it receives, and those selected for a full review will then be subject to a “collaborative,” “independent and impartial investigation” by the unit, in conjunction with the applicant and their attorney.

Terri Rosenblatt, a former public defender who is heading up the PCJU, says the open-application policy is modeled after other progressive prosecutors, including late Brooklyn DA Ken Thompson, who “re-imagined” the role DAs can play in the exoneration process. Thompson, who died of cancer in 2016, aggressively investigated wrongful conviction claims: During his short time in office, his Conviction Review Unit (CRU) became one of the best-resourced in the nation and exonerated 10 people in its first year alone, according to NBC News.

“Before DA’s offices started embracing open-minded conviction review procedures, the typical recourse was that someone who believed they were wrongfully convicted would have to go through the litigation process. And the litigation process is full of procedural roadblocks,” Rosenblatt explained. “That wound up with innocent people spending years or sometimes even decades in prison that they shouldn’t have.”

Bragg, a former deputy to the state attorney general, campaigned for the DA’s office on the promise of reform. (His first few months in office have been rocky, in part because of that reform-mindedness: Bragg’s penchant for pursuing alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent offenses stirred critics who’ve accused him of being too soft on crime.)

Beefing up the office’s conviction review efforts was one of the many overhauls Bragg pledged to tackle. His campaign website took his predecessor to task over the fact that Vance’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU), established in 2010, lagged behind the Brooklyn DA on its number of exoneration cases.

“The existing CIU in Manhattan appears to be a CRINO,” Bragg’s campaign website reads, referring to an acronym for ineffective CIUs—”conviction review in name only.”

Bragg says his PCJU adopts “the best practices” of conviction review offices around the country, and will prioritize cases in which the applicant is still prisonor under parole or post-release supervision. In addition to the review investigations, the unit will offer “support to exonerees, as well as victims and survivors.”

Reviewing convictions in a meaningful way allows DA’s offices to not only correct past injustices, but to examine the mistakes made by earlier prosecutors to avoid repeating them in the future, Bragg said.

“It provides a moment of reflection for the office to carry forward lessons learned during the review,” he explained, saying that work also helps restore public confidence in the legal system. “In some ways, all of our work is centered around community trust, because the system doesn’t work unless there’s trust.”

Rosenblatt said their approach to is reflective of a larger trend of prosecutor’s offices “embracing a just culture,” which includes “recognizing everyone who is system-involved has humanity.”

“And that means that system actors from all sides are human and capable of making mistakes,” she added. “I think that that’s not inconsistent with also knowing that the vast, vast majority of work that all prosecutors offices do is with the utmost integrity and justice-mindedness.”

More information on the PCJU and how to submit an application for a conviction review can be found here.