‘By training and paying students to support their peers on the path to college, not only do schools reduce their student-to-counselor ratio, they also make an investment in the student leaders themselves.’

Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office

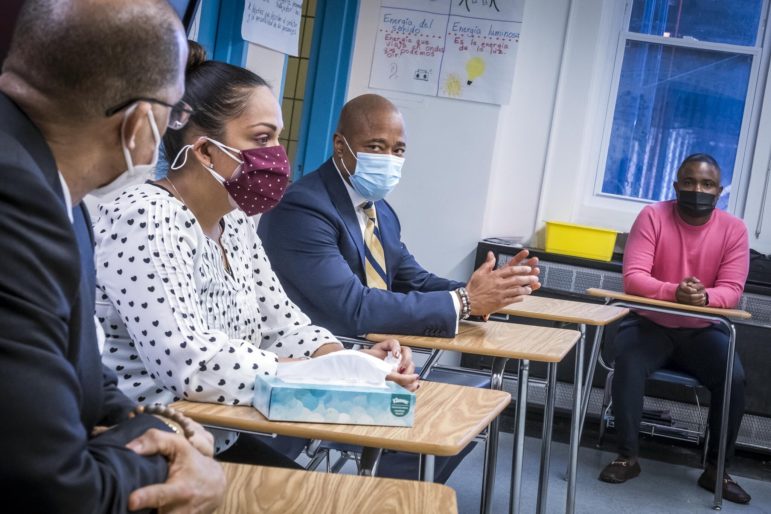

Eric Adams visiting a school in The Bronx last week.New York’s new Mayor Eric Adams and his Schools Chancellor David Banks have pledged to seek input from students as they work to improve city schools. Adams took a significant first step towards that commitment when he created his education transition team, which includes an unprecedented four students as co-chairs and an additional 50 CUNY students as interns.

However, to truly address the persistent inequality in the city’s schools, he should not only listen to students but also empower them as change-makers by expanding the use of paid peer leaders in New York City schools.

Trusting and employing young people to be leaders in schools can have stunning results. At CARA, every year we train and place over 200 high school and college students in paid positions to support their peers on the path to college. This has increased post-secondary enrollment at participating schools by an average of 13 percent, and it gives young people agency to impact the issues that are important to them. As a peer leader from DeWitt Clinton High School in The Bronx reflected, “in communities of color we are used to having a lack of resources,” but by doing this work we realize “we are the resource.”

Heading into 2022, school principals at over 140 schools across the city have adopted this approach, in partnership with CARA and other community-based organizations. Many groups now use a similar peer-to-peer model for a range of school support initiatives, and the NYC Department of Education and CUNY have hired peer leaders to serve students during the transition between high school and college.

City funding for these efforts, however, has historically been sporadic, leaving many programs in jeopardy. To support these programs and to address the persistent inequality in city schools, we call on Mayor Adams and Chancellor Banks to create a sustained, permanent investment in programs that position students as paid peer leaders.

Importantly, peer leader programs align with Adams and Banks’ own educational goals. The new administration wants to improve college and career pathways, yet a major obstacle is a crisis of trust—surveys find that students have lost faith that their investment in education will pay off. Employing students as peer leaders helps rebuild confidence in education. Peer leaders are credible messengers about the value of education because they speak the languages of their communities and are “living testimony” of making it to and through college. As one college counselor who supervises peer leaders explains, “they reach students in a way that we’re just not able to.”

Adams and Banks have also vowed to improve outcomes for low-income students and students of color by using a culturally responsive curriculum. One of the most profound impacts of a peer leader program is the way it builds community and embraces students’ cultures. While peer leaders need professional training and supervision (and thus adequate funding for school staff is essential), the engine of this model is empowering students who are predominantly low-income and students of color to draw on their own knowledge and experiences to support themselves and others like them.

Finally, Banks and Adams have called for allocating resources to students rather than administration. In this regard, money spent on peer leaders is a double investment. By training and paying students to support their peers on the path to college, not only do schools reduce their student-to-counselor ratio, they also make an investment in the student leaders themselves. In CARA’s experience, nearly all high school students who work as peer leaders enroll in college and they are 11 percent more likely to persist in college than their peers. This role also provides much-needed income to students and their families and is an invaluable professional experience.

New York City students have shown a tremendous ability to support themselves and their peers on the path to college. We are glad that Mayor Adams and Chancellor Banks have made an important first step towards recognizing this capacity by including students on the education transition team. But, addressing the persistent racial and economic inequality in New York City schools will require a greater investment in students and a deeper trust in their capacities as leaders.

Charting the path forward for city schools should include involving students in their communities’ futures by training them as peer leaders, paying them fairly for their work, and capitalizing on the knowledge and strengths they bring. The new administration can begin by making permanent the funding for existing peer leadership programs and expanding these programs so that every student in New York City receives the support they need to attain post-secondary success.

Reid Higginson, PhD is the senior research and policy associate at CARA (College Access: Research & Action)