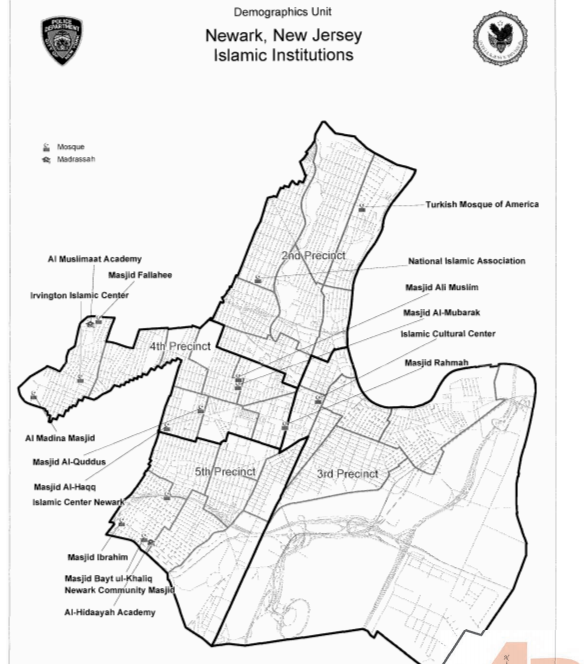

AP/NYPD

A page from one of the documents produced by the now-closed Demographics Unit.

New York State’s freedom of information law, an essential tool for holding government accountable and checking abuses on power, presumes that just about all the information generated or held by government should be released upon request. But there are sensible exemptions to “FOIL,” like for ongoing law-enforcement investigations: Obviously, you can’t ask the NYPD for a list of the drug-dealers it plans to arrest this weekend.

Any person can use FOIL by sending a letter to city or state agency detailing the records sought. The agency is then supposed to tell you whether it has the records you’re asking for and whether you can have them (in other words, whether or not they fall under one of the exemptions in the law). On Thursday, the New York Court of Appeals—the state’s highest court—authorized the NYPD to provide a different sort of answer to FOIL requests: saying that it neither confirms nor denies the existence of the requested records, but that it wouldn’t have to hand them over in any case because they are exempt.

The case involved separate requests by two men, Talib Abdur-Rashid and Samir Hashmi, for information on whether the NYPD had files pertaining to investigations or surveillance of them. The two men were motivated by the revelations of an NYPD “Demographics Unit,” launched during the Bloomberg administration, that reportedly conducted broad-brush surveillance of Muslim and Arab New Yorkers. The men presumably wanted to see if the city had violated their rights by subjecting them to surveillance merely because they were Muslims.

The NYPD refused to confirm or deny any relevant records existed, so the men sued, and now the courts have sided with the cops. The reasoning: There are times when even revealing the existence of records would undermine the purpose of the law-enforcement or public-safety exemptions to FOIL.

If I’m a bad guy and want to know whether the cops are on to me, I could FOIL for investigative documents about me, and if the NYPD says “yeah, we have documents about investigating you, but we can’t show them to you because of the FOIL exemption” then I have learned everything I need to know: It’s time to throw my cell phone in the Bronx River, act to silence anyone I suspect is an informant and maybe even execute evil plans before the fuzz moves in to stop me.

Seen that way, the NYPD’s case is reasonable. But what if protecting a real investigation isn’t what the NYPD is doing? What if it is trying merely to cover up wrongdoing on the part of its officers or leaders? After all, FOIL is founded on the idea that citizens have a right to see if the government is telling the truth. When an agency says “you can’t have the documents because they are exempt,” you can sue to force them to prove that they should be exempt. When an agency says, “we may or may not have the documents, but you couldn’t have them any way,” it makes it a lot harder to articulate such a challenge.

Taken together, it made for a complicated case for the court to consider, and the judges’ reasoning laid out in the court’s full opinion, where the chief judge and three others side with the NYPD, two colleagues dissent and one takes issue with both sides. It’s that last judge, Rowan Wilson, who took issue with an aspect of the city’s case that merits more attention.

In an affidavit filed for the case, the NYPD’s then chief of intelligence, Thomas Galati, “averred that the NYPD intelligence strategies are monitored by individuals and organizations with the goal of developing counterintelligence measures, and the greatest vulnerability to the NYPD Intelligence Bureau is the release of even ‘seemingly innocuous information’ which would inexorably reveal sources from which information is gathered by the NYPD,” the court’s majority opinion reports.

Galati’s affidavit sketched out four potential problems with acknowledging the existence of information about terrorism investigations:

1) “The knowledge that a person or group is the subject of a NYPD counter-terrorism investigation would allow that person or group to alter their behavior so as to avoid detection”

2) “Conversely, the knowledge that a person or group is not a subject of investigation would allow such persons to more freely engage in illegal activity”

3) “A person who knows he or she is under investigation might scrutinize his or her contacts more carefully and, in doing so, could discern the identity of an undercover police officer or confidential informant working on the case. Not only would this compromise the integrity and value of any information to be learned from such sources, but it could endanger the lives and safety of such sources”

4) “Disclosure of whether a particular individual or group is the subject of investigation would allow those bent on unlawful activity to prepare a roadmap of investigatory operations, decisions, techniques and information that would enable every group to anticipate investigative tactics and activities, and undermine current and future investigations.”

As Wilson points out, the first three harms “are premised on the conjecture that individuals—presumably other than Mr. Hashmi and Mr. Abdur-Rashid, whom the record suggests are upstanding citizens—inclined to terrorism or organized crime will FOIL themselves, and then tailor the scope of their activities to either stymie investigators or exploit the discovery that they are not (or were not) under investigation.” But the NYPD didn’t “provide any factual basis to conclude that terrorists have used similar information to tailor their activities.” And, Wilson wrote, “Absent such a statement, let alone the evidence thereof that our probing standard would require, it strains belief that terrorists are self-identifying themselves to the NYPD by filing regular FOIL requests.”

The fourth problem is easier to believe on its face, Wilson argued. But how wide and thick a blanket of secrecy does that justify the NYPD throwing over its work?

Concealing current investigations makes sense, but what about probes undertaken several years back? “Given the constant improvements to and alterations in NYPD capabilities and strategies, as well as the significant changes made to the Intelligence Division in the wake of the 2013 mayoral election,” Wilson writes, it’s hard to believe that every old investigation warrants the exemption.

And does the NYPD really have to treat every FOIL-writer like a potential master criminal? “[W]hatever the counter-intelligence capacities of gangsters and terrorists, garden-variety criminals (and law-abiding citizens) are probably not piecing FOIL reports into a jigsaw puzzle depicting the anticipated movements of NYPD officers.”

Wilson lost his argument and the NYPD won the case, but this is hardly a closed issue, because this is not the first time the NYPD has used the alleged threat of terrorist snooping to justify thwarting efforts to improve transparency.

When the City Council considered a bill last to force the NYPD to disclose the kinds of surveillance devices it used and how it was protecting public privacy from unnecessary prying, The NYPD’s deputy commissioner for legal affairs said if the bill passed, “The next issue of Inspire magazine [which is published by Al Qaeda] that came out after it would be devoted to all of the technology the NYPD uses to prevent terrorist attacks — here’s how you can disable these technologies, here’s how you can avoid these technologies.”

The Brennan Center countered that, the law in question “is carefully calibrated to ensure that the NYPD can continue to keep the city safe while providing policymakers with the information necessary for effective oversight … [It] is consistent with federal practice; and the failure to disclose such basic information can actually harm law enforcement.”

This line of argument is different from the NYPD speaking without specificity about terrorist threats to justify counter-terrorism tactics, like searching subway bags or sending officers to a particular location. That’s often understandable. This is about the NYPD speaking generally about terrorist threats to escape being subject to legislative oversight or public scrutiny of past intelligence-gathering efforts aimed at law-abiding people. That’s a little different.

The opinions published yesterday by Judge Wilson and his colleagues on the Court of Appeals are worth a read if only because, given the veil of secrecy they have by a 4-3 vote authorized, it might be the only public airing of these arguments in any detail.