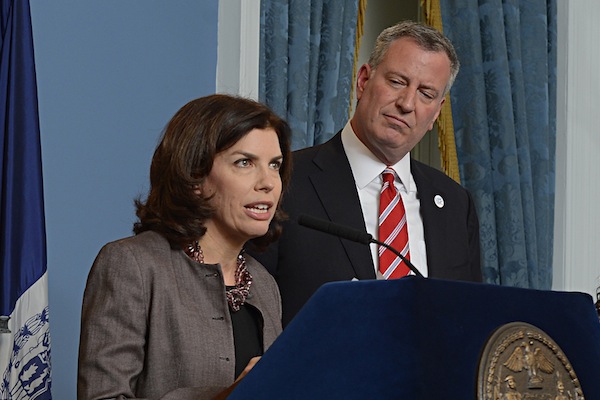

Rob Bennett for the Office of Mayor Bill de Blasio/City Limits

DCA Commissioner Julie Menin with Mayor De Blasio. The city issued 115 subpoenas this summer in an investigation of unlicensed employment firms.

Michael Blount wanted a job and he thought he had found a path to one: A Craigslist ad offering housekeeping work at decent pay in the metropolitan area. So he took the train in from New Jersey to the address on 32nd Street between Park and Madison Avenues. And he brought the $70 he was told he’d need to get the process started.

But soon, he was told he actually needed to pay $100, then $300. All told, he says he paid the firm—which he says called itself PCS—$500.

By September, Blount was growing suspicious. He was asked to fax in a resume. So he faxed his resume. He heard nothing. Later, he missed an appointment and was subsequently told that was the day a recruiter had been on hand. “But I don’t believe it,” he says. “The lady told me she was going to call me. That’s the same thing I heard last time.”

The city’s Department of Consumer Affairs has charged PCS with operating an unlicensed employment agency, and the company faces a November 5 hearing at which it could be fined or padlocked.

That action comes as DCA mounts a crackdown on firms that illegally siphon money from job seekers. This summer the agency subpoenaed 115 such firms. Calling the companies’ conduct “predatory,” DCA Commissioner Julie Menin tells CityLimits.org: “This has an extremely negative impact, particularly on low-income people.”

But the city enforcement spree faces a challenge—namely that businesses cited for breaking the rules for employment agencies can change names with a few key strokes and move from one location to another to keep operating the same alleged scam with a different moniker and address. In the fiscal year that ended in June, the city received more than 200 complaints about employment agencies. It certified 20 violations.

Need license to offer services

Maryous Oliver, who appears to lead PCS, insists he is just a contractor of the company and that the business doesn’t need a license. “We are not an ’employment agency,'” he said during a brief interview. “We are an agency that provides training that creates an opportunity for employment.”

By state law, firms that charge a fee to “procure or attempt to procure employment or engagements for persons seeking employment or engagements, or assist employers in procuring employees” must be licensed by the city as employment agencies. Getting a license requires a substantial amount of documentation and a fee.

The law also regulates what an employment agency can and cannot do. An employment agency “can’t charge for training or certification of any kind as a precondition for employment,” Menin says. If a firm does that, or guarantees you a job, or asks about age, immigration status or nationality—questions that are prohibited by law—”These are the kind of things that should immediately raise a red flag,” she says.

An unlicensed agency can be fined $100 a day beginning the day a DCA inspector cites it. Other violations of the law can come with a fine of $350 per count. A business can also be padlocked, Menin says, for running afoul of the law. Last fiscal year the city ordered $17,000 in restitution and $177,000 in fines.

The name game

But it’s not clear how many of those fines were actually collected. More fuzzy is whether the punishments actually stopped illegal conduct, or merely prodded shady firms to change their name and location.

“The challenge is in the fly-by-night nature of these businesses,” the commissioner says. “For many of these unlicensed operations, they are literally moving from place to place to place overnight.” For the most part, Menin says, DCA violations are against a business, not an individual.

Oliver, for instance, has been associated with firms like Allstate Secure Force and Secure Force, according to DCA. Multiple postings on consumer-watch websites also link him to USA Resource Solutions, Dynamic Resource Solutions and Corper Security. Earlier this summer, Oliver was caught on hidden camera and then cornered by ABC News for a story about employment scams. It didn’t appear to slow him down.

DCA also can refer cases to the district attorney’s office for prosecution. In late 2013, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance announced the conviction of four people associated with a firm called Allianz Security Protection LLC on felonies related to stealing application fees from job applicants. Three of them are now serving terms in state prison.

While DCA couldn’t say how often those referrals happen, a spokeswoman wrote, “The de Blasio administration is looking to expand its partnership with the DA’s office and increase the number of referrals.” Menin says the issue came up in a recent meeting with Vance.

Menin recommends that anyone considering paying a firm for employment services first check the DCA website to see if they are licensed. Clients who go to an agency and think it engaged in illegal activity can file a complaint with DCA here.

Training agencies licensed by state

While DCA licenses employment agencies, security training agencies are licensed by the state Division of Criminal Justice Services. None of the companies that DCA or consumer-alert sites associate with Oliver are licensed to provide security guard training. (DCJS advises people looking for such training to check here to make sure the trainer is licensed.)

At the hearing in November, PCS will be able to contest a violation issued in September for allegedly offering employment services for a $75 fee to a DCA inspector. One of the other firms DCA associates with Oliver, Secure Force, was also inspected by the city and no violations were found; DCA says the investigation continues.

PCS’s ads certainly make the firm sound like an agency that links people to jobs. A current posting calls for “lobby monitors” and discusses compensation levels and required “job skills and responsibilities.” Another reads: “Need security officers to work at the front desk with understanding of cameras, computer, phone system and possessing excellent client support skills. … Males and females needed. First time job seekers are welcome. Experience is a plus.” Yet another ad, listing the same phone number as the others, calls for armored-car drivers. “We will provide the right candidate with the training and all required handgun licenses,” it reads.

Oliver says he is just a contractor for PCS solutions, not a principal of the company, though he declined to put a reporter in touch with his superiors. Asked if his clients ever get jobs, he says, “It’s up to you what happens in an interview. I can’t control that.” His retort to clients who feel PCS scammed them is that each of them signed a contract accepting that landing a job was their responsibility, not the firms’.

As to why his operations are so well-known to DCA, Oliver says his visibility merely reflects the fact that he has been in this business a long time—10 years, by his count. “When you do more volume, circulate 20,000 to 30,000 flyers, you become more widely known,” he says.